Understanding Git (Part II): Working with Remotes

In this post, I explained the very basics of Git. There was only one repository in your local machine and only one person making changes. That is well and good, but in practice many programmers contribute to a project: each needs a copy of the repository and many changes are made simultaneously. Version controlling these distributed projects is a big problem that Git solves brilliantly!

In this post, I will explain how this works and how you can use Git remote repositories without shooting-yourself-in-the-foot. I only assume that you are already familiar with the very basics of Git like commits and branches.

NOTE: These are the post in the Understanding Git series:

Remotes

Git relies on servers to version control a distributed project. The server

manages the order in which changes are versioned and provides a consistent

view of the files in the repository. The Git server also allows programmers to

download local copies of the repository using the git clone <address>

command.

Nowadays, it is popular to host Git repositories on the internet using websites like GitHub, GitLab or BitBucket. The website acts as the Git server for a project. For example, I can make a local copy of RISC-V’s Spike’s simulator, which is hosted in GitHub, like this:

git clone https://github.com/riscv-software-src/riscv-isa-sim.git

On success, Git will download, a.k.a clone, the repository and store it in my

computer at a directory called riscv-isa-sim. As discussed before, Git

repositories have a main branch which is called master in Spike’s case, so

Git will checkout that branch right after cloning. You can check that with git

branch.

From Git’s point of view, your clone is just a local copy of the repository

which tracks Spike’s remote repository in GitHub. You can check this with

git remote that outputs the following for my Spike clone:

$ git remote -v

origin https://github.com/riscv-software-src/riscv-isa-sim.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/riscv-software-src/riscv-isa-sim.git (push)

After cloning, you will contact the repository for either of two reasons. You

can upload, a.k.a push, new commits, i.e. changes, that you made or you can

download, a.k.a fetch, commits that others have pushed to the remote since

the last time you fetched. git remote is telling us that Git will contact

the server at that HTTPS URL for either pushing or fetching. Git helpfully calls

the remote origin so we do not have to keep typing that long URL!

Branches and Remotes

Recall that a branch is simply a pointer to a commit and that you can create

an arbitrary number of branches with git branch. Newly created branches are

only local to your repository until you push them to the Git server. In fact,

there are two sets of branches in my Spike clone repository: your local

branches and the remote’s branches! You can see all branches with:

$ git branch -a

* master

remotes/origin/HEAD -> origin/master

remotes/origin/confprec

remotes/origin/cs250

...

The first line of output says that there is a local branch called master that

is currently checked out, hence the *. If I were to create a new commit at

this point, master would point to the new commit. The following lines start

with remotes/origin/ meaning that these branches belong to the remote called

origin i.e. the GitHub remote repository. Line 2 is special for two reasons:

origin/masteris the server’smasterbranch.remotes/origin/HEADindicates the remote branch checked out when cloning.

When we said that Git “checked out” master after cloning, what happened is

that Git saw that remotes/origin/HEAD pointed to origin/master, so it

created a local branch, i.e. a pointer, called master which points to the

same commit that origin/master references.

You can create local copies of other remote branches with git checkout. For

example, git checkout confprec will create a local branch confprec pointing

to the same commit that origin/confprec does. You can also checkout the

commit that origin/confprec points to with git checkout origin/confprec.

However, you cannot directly make a remote branch point to another commit

(e.g. by using git commit) because git checkout origin/confprec will

actually set the repository into detached state like this:

$ git checkout origin/confprec

Note: switching to 'origin/confprec'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by switching back to a branch.

...

$ git branch

* (HEAD detached at origin/confprec)

master

Multiple Remotes

You can configure an arbitrary number of remotes in your local repository. Each

remote will have its own set of remote branches. For example, there would be

three sets of branches if I had two remotes: one set of local branches and two

sets of remote branches. Again, recall that remote branch names are prefixed

with the remote’s name so that <remote_name>/master is a remote branch while

master is a local branch.

I will discuss why having multiple remotes helps and how to use them in a future post.

Pushing to Remotes

As we discussed, we cannot directly modify the remote’s branches in our local repository, so how do we create new commits and push them to the server? The process is actually very simple:

- Checkout a local branch, for example,

git checkout master - Make your changes

- Create a new commit in

masterwith the changes usinggit addandgit commit, and perhapsgit mergetoo! - Run

git push <remote_name> <branch_name>, sogit push origin masterin this case.

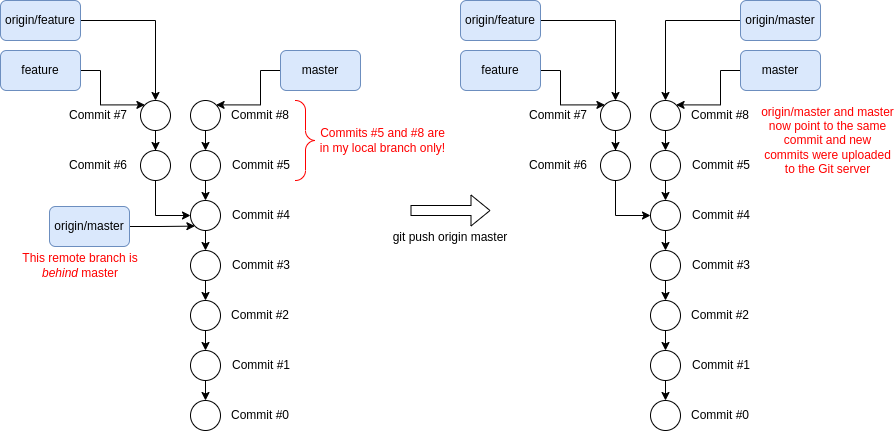

After running git push, Git automatically understands that your local

master branch is tracking the remote’s origin/master branch, so Git will

upload any new commits to the server and set origin/master to point to the

same commit as master as shown below. In the case that you are pushing

commits in a new branch my-new-branch that the server does not know about,

Git will upload the new commits and create a origin/my-new-branch branch.

Once you pushed, anyone will be able to see your new commits, and potentially a

new branch, in the Git server.

Before and after pushing new commits in the local master branch to the Git server at origin.

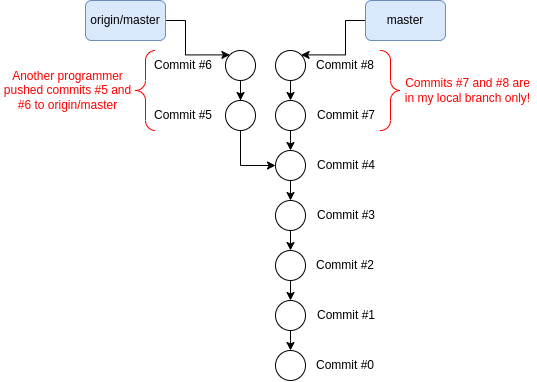

git push will throw an error if you try to push commits to a remote branch

that cannot be fast-forwarded. For example, this occurs when another programmer

pushes a commit to origin/master before you push your own changes in the

local master branch; in other words, origin/master and master diverged

as shown below. If this happens, simply fetch from the remote (see below!),

update your local branch with the latest changes (using, e.g., git merge or

git rebase) from the remote branch that it is tracking and try to push again.

git push fails because origin/master and master branches diverged.

Fetching From Remotes

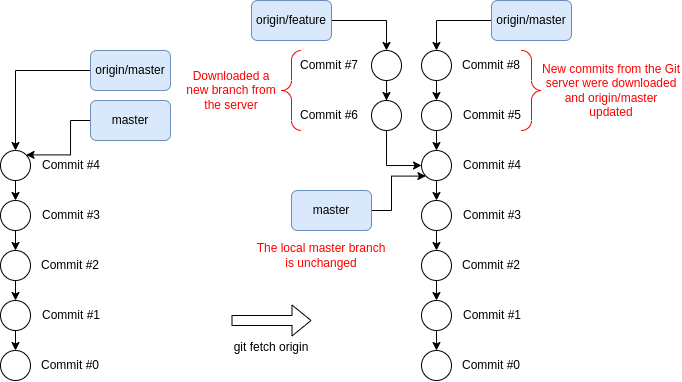

We obviously want to regularly download the latest changes that others have

pushed to the server. We can do that with git fetch, for example, git fetch

origin in the case of my local Spike repository. Git will download the latest

commits from the server and update the remote branches i.e. the branches

prefixed with origin/.

After git fetch, the remote branches in my local copy of the repository are

synchronized with the server, but my local branches will be left untouched as

shown below.

Git history before and after git fetch origin. New commits and branches are downloaded from origin while local branches are unchanged.

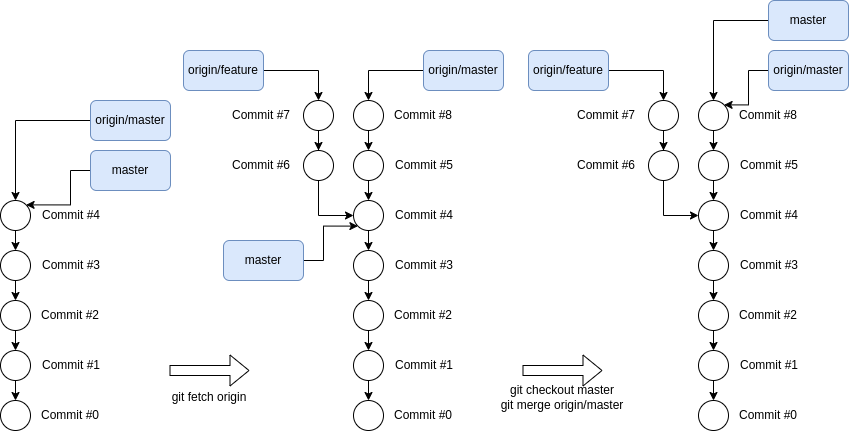

You can update your local branches to point to the latest commit if you wish to

with git merge or git rebase just as discussed in this previous post. For example, the figure

below shows the history of a repository before and after fetching and merging

with:

git fetch origin

git checkout main

# Fast-forward main to reference the same commit as origin/main

git merge origin/main

Git history after fetching from origin and fast-forwarding master to reference new commits in origin/master.

Pulling: Fetching + Merging

git pull is a convenience command that combines the fetching and

merging/rebasing functions into one (see documentation

here). I seldom use it because I rarely

ever update my local branches! I will explain why in a future post. I also

think that git pull does a lot behind the scenes and this tends to trip new

users, so I would recommend that you avoid it if you are new to Git.

Visualizing Git History

It can sometimes be helpful to visualize your Git history as the project grows

with many commits, branches and remotes. Of course, you can use the venerable

git log (see documentation here), but

there are also many tools to assist you with this, such as

gitk, GitKraken

or Sourcetree. My favorite visualizer is

tig, which stands for Text-mode Interface for

Git, because it is light-weight, easy-to-use and works directly in the

terminal. Here is a great blog

post about tig if you are interested!

Conclusion

You should now be familiar with how Git tracks remote repositories using branches if you made it this far. We also covered how you can clone repositories from a server as well as fetch the latest changes and push your new commits to the server. In the next post, I will describe the workflow that many Git open-source projects use.